↑

The Canto General :

compositions de Mikis Theodorákis sur des poèmes de Pablo Neruda

(Neruda Requiem Aeternam : paroles et musique de Mikis Theodorákis)

Texte original Heredero de Pablo Neruda, 1950, Fundación Pablo Neruda

Ediciones Cátedra, 1a edición 1990, 12a edición 2009, Madrid

Traduction Claude Couffon

Nrf Éditions Gallimard, 1977

Algunas bestias

Vegetaciones

Vienen los pájaros

Voy a vivir

Neruda Requiem Aeternam

Los Libertadores

La United Fruit Co

América insurrecta

Algunas bestias – Some animals

⇑

|

Era el crepúsculo de la iguana. Desde la arcoirisada crestería Los monos trenzaban un hilo Era la noche de los caimanes, El jaguar tocaba las hojas Los tejones rascan los pies Y en el fondo del agua magna, |

It was the dusk of the iguana. From the rainbowed peaks The monkeys wove a thread It was the night of the caimans, The jaguar touched the leaves The badgers claw the feet And in the depths of great waters, |

In 1980, with Maria Farantouri

In Algunas Bestias, Pablo Neruda’s celebrates the wildlife of South America.

This poem, rich in vivid and sometimes brutal descriptions, highlights the diversity and power of nature, while suggesting a deep connection between humans and the animal world. Neruda’s approach is both naturalistic, describing the physical characteristics and behaviours of animals, and symbolic, using beasts to express ideas about freedom, strength, fragility, and the struggle for survival.

This poem offers a striking representation of the Amazon rainforest at dusk.

It depicts the interaction of various creatures, each with distinct characteristics. The iguana’s tongue is darted like a weapon, anteaters walk with rhythmic precision, and the guanaco’s golden hooves leave a trail in the twilight.

The poem evokes a sense of primal energy and the interdependence of life.

Caimans emerge from the depths, armed and ready for the night hunt. The phosphorescent absence of the jaguar and the fiery pursuit of the puma create an atmosphere that is both beautiful and dangerous. The relentless night hunt of the tejones – badgers – highlights the harsh realities of the rainforest ecosystem.

Neruda’s use of imagery and symbolism is particularly striking in this work.

The “círculo de la tierra” alludes to the ancient and mystical significance of the serpent. The “barros rituals” suggest the sacred nature of the anaconda’s role in the ecology of the rainforest.

Compared to Neruda’s other works, this poem shares his concern for the natural world and humanity’s connection to it. However, it stands out for its more explicit celebration of the primitive and wild aspects of the rainforest. The poem reflects the growing environmental awareness of its time, capturing the wonder and amazement inspired by the rich biodiversity of the Amazon rainforest.

Vegetaciones – Plants

⇑

|

A las tierras sin nombres y sin números |

To lands without names, without numbers, |

|

En la fertilidad crecía el tiempo. |

In this luxuriance time grew. |

|

El jacarandá elevaba espuma |

The jacaranda raised up a froth |

|

Un nuevo aroma propagado el tabaco silvestre alzaba Como una lanza terminada en fuego Arruga y extensión, diseminaba Y aún en las llanuras |

A new aroma spread, the wild tobacco raised Like a spear with a fire tip, Wrinkle, expanse: the seed And in the plains, again, |

|

América arboleda, |

Forested America, |

|

Germinaba la noche Útero verde, americana |

The night germinated Green womb, American savannah |

Vegetaciones is a celebration of nature and the American land.

It describes nature as a living and powerful force, a ‘green treasure’ that contains vital and creative energy. The poem praises wild and lush nature, and establishes a deep connection between nature and American identity.

Nature as a source of life: Neruda uses powerful imagery to describe vegetation as a creative and life-giving force.

He speaks of “plant gods”, “germinating stones”, and “births”.

America as a lush land: the poem highlights the richness and diversity of American vegetation, describing it as an “grove” and a “green treasure”.

Man and nature: the poem establishes a close connection between man and nature, suggesting that nature is an integral part of American identity and the human experience.

Vegetaciones can be seen as an ode to the American land, celebrating its natural beauty and strength.

The poem calls for the protection of this environment and recognition of its value.

It highlights the simple, raw beauty of nature, in contrast to the complexity and violence of the modern world.

In short, Vegetaciones is a poem that celebrates nature as a vital force, a symbol of American identity and a source of inspiration for mankind.

Vienen los pájaros – The birds are coming

⇑

|

Todo era vuelo en nuestra tierra. Como gotas de sangre y plumas El tucán era una adorable caja de frutas barnizadas, |

All was flight on earth. Like drops of blood and feathers

|

|

Los ilustres loros llenaban la profundidad del follaje |

Magnificent parrots filled the depth of the foliage |

|

Todas las águilas del cielo nutrían su estirpe sangrienta |

All the eagles of the sky nurtured their bloodthirsty kind |

|

La ingeniería del hornero hacía del barro fragante El atajacaminos iba dando su grito humedecido La torcaza araucana hacía ásperos nidos matorrales |

The ingenious hornero built of fragment mud The atajacaminos flew by and uttered its humid cry The araucanian dove built her thorny nest in the brambles |

|

La loica del Sur, fragante, dulce carpintera de otoño, |

The starling of the South, fragnant, gentle carpenter of autumn, |

|

Mas, húmedo como un nenúfar |

And, wet as water lily, |

|

Vuela una montaña marina hacia las islas, |

A sea-mountain of birds fly toward the islands, |

|

Es un rio de sombra, |

It is a living flood of shadows, which darken the sun of the world |

|

Y en el final del iracundo mar, en la lluvia del océano, |

And at the limits of the irascible sea, in the ocean’s rain, |

Live From Athens / 1975, with Maria Farantouri

Vienen los pájaros describes a world where flight is omnipresent, where birds of all kinds populate the sky and the earth.

The poem celebrates the beauty and diversity of the avian world, while evoking the strength and power of nature.

The omnipresence of flight: The poem opens with a strong statement: “Everything was flight on our earth”.

This sentence establishes flight as an essential characteristic of the world described by Neruda.

The diversity of birds: Neruda describes with precision and poetry a variety of birds, from cardinals to toucans, hummingbirds to parrots, eagles to condors.

Each bird is described with strong and original imagery, emphasising their individuality and beauty.

Poetic imagery: The poem is full of vivid and colourful images, such as “the scarlet cardinals bled the dawn of Anáhuac” or “the parrots were like ingots of green gold”.

These images contribute to the sensory richness of the poem and the power of its description of the world.

Nature as a source of inspiration: The poem celebrates nature and its power, particularly through the description of the condor, “murderous king, solitary brother of the sky, black talisman of the snow, hurricane of falconry”.

This description highlights the strength and majesty of nature, but also its mystery and danger.

Neruda’s commitment: As is often the case in Canto General, Neruda uses descriptions of nature to express his political and social commitment.

By describing the beauty and power of the world, he calls for the protection of nature and the defense of oppressed peoples.

Voy a vivir – I will live

⇑

|

Yo no voy a morirme. Salgo ahora Aquí dejo arregladas estas cosas Aquí me quedo con palabras y pueblos y caminos |

I shall not die. I go out, I leave these things in order behind me Here I stay with words and people and roads |

Voy a vivir – A cry for life:

The title, “I will live”, is a true act of faith, a powerful affirmation of his will to live and to commit himself.

The poem is written in a context of political and social unrest, particularly in Spain and Chile, where Western culture is associated with violence and oppression.

Neruda rejects death in all its forms, whether physical (the ‘gangsters’ and ‘scaffolds’) or symbolic (passivity and renunciation).

The poem is a declaration of his political commitment, a way of saying that he will not be intimidated by violence and injustice.

The author expresses his love for life, for the world and for his people. He wants to live life to the fullest, despite the difficulties.

The style is simple, accessible, yet powerful, with strong images and striking metaphors.

Voy a vivir is a poem vibrant with life and hope, a testament to the strength of the human spirit in the face of adversity. It is a call to action, to fight for a better world, and to love life in all its forms.

Neruda Requiem

⇑

|

Neruda Requiem Æternam. Lacrima yá tous zontanous Lákrimosa Neruda Requiem Æternam. |

Neruda Requiem Æternam. Tears for the living Lacrimosa (torrent of tears) Neruda Requiem Æternam. |

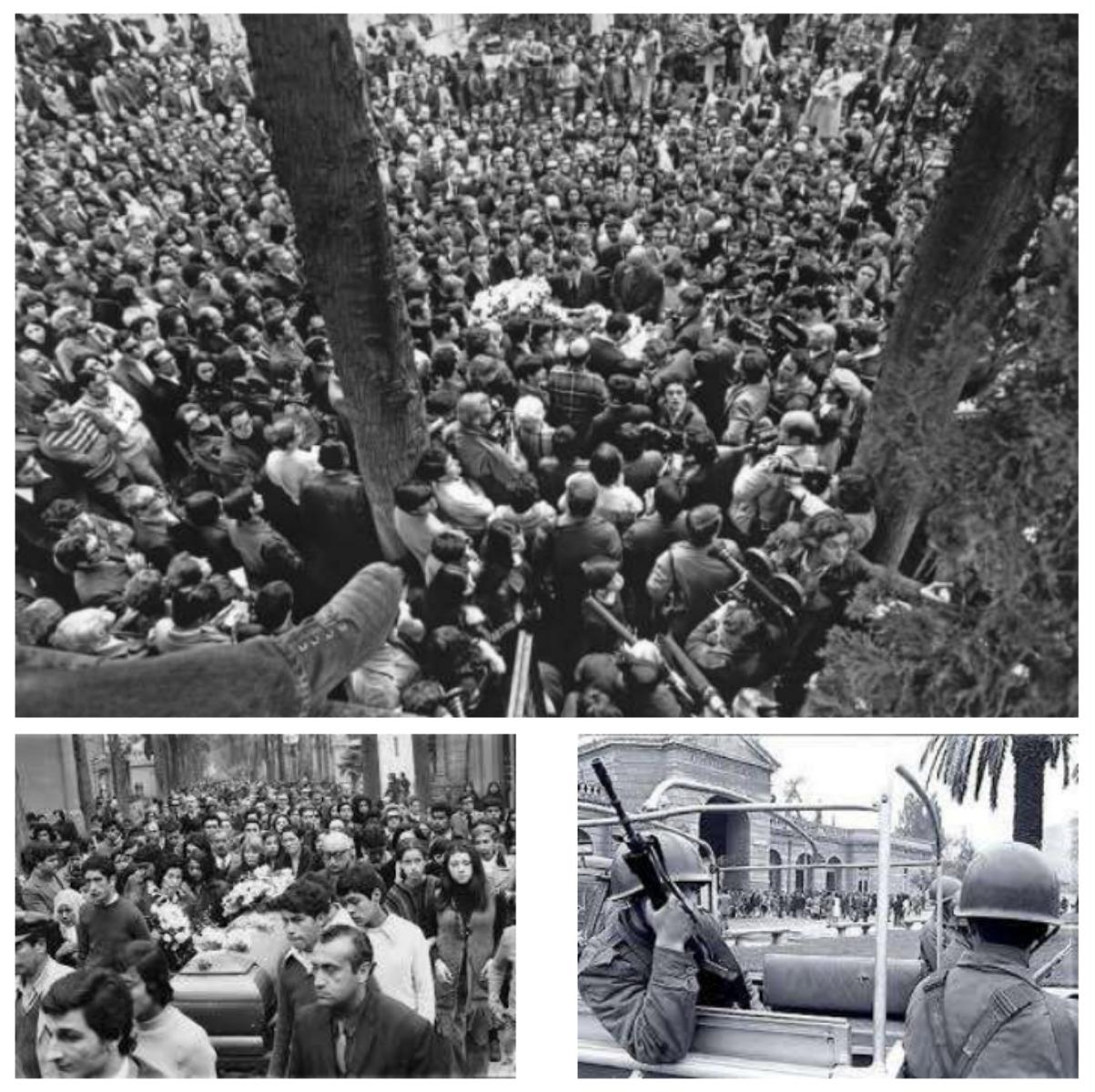

Suffering from prostate cancer, Pablo Neruda died on 23 September 1973 in a clinic in Santiago, Chile.

The dissident communist poet thus passed away twelve days after Augusto Pinochet’s coup d’état.

Following the coup d’état of 11 September 1973 and the assassination of President Allende, he died 10 days after his friend. The thousands of Chileans who accompanied the poet to the cemetery, surrounded and escorted by the secret police and armed soldiers, shouted:

“Camarada Pablo Neruda, Presente! Ahora y siempre! ”

The mystery of Pablo Neruda’s death

Disappeared in the early days of Augusto Pinochet’s regime, did the famous Chilean poet really die of cancer or was he murdered by the military? A look back at fifty years of investigation into one of the greatest mysteries of the Chilean dictatorship.

The story. Suffering from prostate cancer, Pablo Neruda died on 23 September 1973 in a clinic in Santiago, Chile. The dissident communist poet disappeared twelve days after Augusto Pinochet’s coup d’état. Coincidence? Many observers at the time refused to believe it.

For them, there is no doubt that Pablo Neruda was assassinated by the military dictatorship a few days before he left for Mexico, where he could have become the face of opposition to the regime. The author retraces the different stages of the investigation: from the analysis of the death certificate to the exhumation of the body and the opening of a judicial inquiry in 2011.

The interest. The investigation delves into the dark hours of the Chilean dictatorship by interviewing key figures of the time, including Pablo Neruda’s former driver, Manuel Araya, who is still alive. He thus bears witness to the man who was his boss, winner of the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1971 and a huge cultural figure in Chile. This book is also proof that, despite several in-depth investigations, Chile continues to encounter numerous difficulties in shedding light on the dark years of its history.

By Marion Torquebiau

Published Dec.7, 2023

Los Libertadores – The Liberators

⇑

|

Aquí viene el árbol, el árbol De la tierra suben sus héroes |

Here comes the tree, From the earth its heroes rise |

|

Aquí viene el árbol, el árbol |

Here comes the tree, |

|

Aquí viene el árbol, el árbol las elevó por sus ramajes, Fueron flores invisibles, |

Here comes the tree, raised them to its branches, There were invisible flowers, |

|

Y el hombre recogió en las ramas |

And mankind gathered from the branches |

|

Éste es el árbol de los libres. El árbol tierra, el árbol nube, Lo ahoga el agua tormentosa |

This is the tree of the free people. The tree of earth, the tree of cloud, It drowns in the stormy waters |

|

Otras veces, de nuevo caen así pasó desde otros tiempos, Éste es el árbol, el árbol |

Sometimes its branches fall anew, thus it was in other times, This is the tree, |

|

Asómate a su cabellera: hunde la mano en las usinas Levanta esta tierra en tus manos, |

Lean on its mane : plunge your hand into its factories Lift this world in your hands, |

|

Defiende el fin de sus corolas, |

Defend the purpose of the petals, |

Los Libertadores reflects Neruda’s political commitment, his solidarity with oppressed peoples and his vision of a Latin America united in its struggle for freedom.

Neruda’s writing combines the beauty of landscapes with the violence of history, tenderness with imprecation, simplicity with vehemence.

Theodorakis, known for his political commitment and his popular Greek music, breathes new life into Los Libertadores by creating an oratorio that highlights the poetic power of the text.

Theodorakis uses an ancient, omnipresent choir to highlight the essence of Neruda’s poems.

The soloists, for their part, clarify the text and emphasise the important themes.

Los Libertadores is an example of the artistic collaboration between Neruda and Theodorakis, where the former’s committed poetry meets the latter’s musical power to create a committed and moving work of art.

La United Fruit Co

⇑

|

Cuando sonó la trompeta, estuvo La Compañía Frutera Inc. Bautizó de nuevo sus tierras enajenó los albedríos moscas Trujillos, moscas Tachos, Entre las moscas sanguinarias Mientras tanto, por los abismos un cuerpo rueda, una cosa |

When the trumpet sounded The United Fruit Company It rebaptized these countries it abolished free will, Trujillo flies, Tachos flies With the bloodthirsty flies Meanwhile the Indians fall a corpse rolls, a thing without |

In this poem, Neruda condemns the United Fruit Company for its exploitation of Latin America.

He depicts the downside of the banana trade and its consequences for citizens. In doing so, he suggests that the United States exploits the misery and degradation of Latin American peoples through this destructive enterprise.

The United Fruit Company also became the title of the collection in which it was included, published in Mexico in 1950.

In a preface, Neruda writes:

“The explanation and confessions of love, rage and hope contain more serious themes ; their purpose is not to unburden me, but to explore the black, rancid and yet beautiful wound of my mysterious country.”

Compiled at a time of profound change, both internal and external, these poems focus on several more specific facets of the general experience of the conquest of Latin America.

The title suggests a commentary on the invasive role of the United States, generally represented by the United Fruit Company.

The United Fruit Company was first published in 1939 in Neruda’s collection “Twenty Love Poems and a Song of Despair”.

During its existence, the company was heavily involved in Latin American politics, and its actions led some to propose entirely new university courses. The company exerted a strong influence over many Latin American countries and was often accused of political intimidation and government manipulation. Despite these serious allegations, it was never found guilty.

In 1970, Neruda expressed his deep disappointment with the course of past history, as Latin America had accepted capitalist-oriented companies.

Throughout his life, Neruda aspired to change. In his will, he left instructions to transform his house into a kind of sanctuary for artists and to place “elementary books on communism” in the houses of the Isla Negra region. This hope for change, nurtured throughout his life, is probably the reason for his enthusiasm in writing this poem.

The United Fruit Company was an American company in the early 20th century involved in extensive imperialist mechanisation.

It is known for its important role in Central American countries such as Guatemala, Costa Rica, Honduras, Nicaragua, and the Caribbean. The United Fruit Company acquired vast tracts of land in Guatemala to grow tropical fruits for millions of Americans. The most widely grown fruit was the banana.

Its production required a considerable workforce, which led to the displacement of most farmers.

This was followed by the abolition of debt bondage, which forced workers to work to repay a loan or debt without being paid, which was a form of slavery. The United Fruit Company mainly used this type of slavery to force indigenous people to work in the fields. When the company imposed a property tax increase, the Guatemalan people’s anger exploded, which is partly why United Fruit shifted its operations to Costa Rica. It was not until the late 1930s that the Guatemalan government, increasingly exasperated by the depletion of the country’s resources, developed strategies to recover them.

In Costa Rica, the United Fruit Company spent millions of dollars on propaganda and advertising campaigns to raise awareness of the benefits of its presence. At one point, company officials even met with President Figueres to suggest that “due to the global economic crisis, the company should take control of the government” (Gudger).

The United Fruit Company ultimately suffered a major setback in Costa Rica with the advent of the Latifundia Law.

JW stated: “I believe that the Latifundia Law has done us more harm than any other event in our history in Costa Rica” (Gudger).

Despite these measures, the United Fruit Company realised that the future of its business was indeed compromised.

It therefore turned to its most valuable asset and the place where its influence was considered to be most profound: Honduras. It was here that United Fruit was able to exasperate the population and the government more than anywhere else, to such an extent that the entire history of the region revolved around the company.

Pablo Neruda was born in 1904 in Parral, Chile. He was well informed about the company’s activities regarding the national sovereignty of Latin American countries, and he was also aware of how the US government intervened to provide temporary, then immediate, “assistance” to companies with interests in Latin America.

Neruda had first-hand experience of imperialism in Ceylon, where he was appointed honorary consul. It was there that he observed how United Fruit and other companies managed to take control of Latin American countries by exploiting their resources and forcing people to work for extremely low wages in order to survive.

This event in Ceylon made Pablo Neruda aware of similar incidents in Latin America and led him to write the poem The United Fruit Company at the end of his life.

By recounting the experiences of different nations and the tragedies of his people, Pablo Neruda highlights various examples from around the world of the negative influence of fruit companies such as UF on the culture, resources and development of many nations, right up to modern societies.

América insurrecta – Rebellious America

⇑

|

Nuestra tierra, ancha tierra, soledades, Una callada sílaba iba ardiendo, |

Our land, our wide land, desolate, A silent syllable took fire, |

|

Fue dura la verdad como un arado. |

The truth was hard as a plow. |

|

Rompió la tierra, estableció el deseo, Fue callada su flor, fue rechazada |

It tore open the earth, established desire, Its flower was silenced, |

|

El pueblo oscuro fue su copa, Y salió con las páginas golpeadas Hora de ayer, hora de mediodía, |

The people of the shadows were its chalice, And they came forth with beaten flanks, |

|

Patria, naciste de los leñadores, |

Fatherland, born of woodsmen, |

|

Hoy nacerás del pueblo como entonces. |

Today you shall be born of the people as before. |

|

Hoy saldrás del carbón y del rocío. Hoy llegarás a sacudir las puertas con herramientas hurañas |

Today you shall emerge from the coal and the dew. Today you will come and beat on the doors |

América insurrecta depicts the struggle of the peoples of Latin America against oppression and injustice, celebrating their thirst for freedom and their resistance.

An analysis of this poem reveals a vibrant call to action, a glorification of popular strength and a denunciation of foreign domination and authoritarian regimes.

The poem is a hymn to revolt, in which the oppressed rise up to break their chains.

The images of “rumours” turning into “gallops” and hidden “flags” emerging to “crack the walls of prisons” illustrate this transformation from passivity to action.

Neruda highlights the power of the people, capable of rising from the ashes, forging a new identity from the “earth”, “coal” and “dew”. He emphasises the importance of popular unity in the struggle for freedom.

Denunciation of oppression: The poem strongly criticises oppression, whether colonial or authoritarian. It denounces the “woodcutters” and “carpenters” who, in the past, contributed to the construction of an oppressive system, but who, today, can also be the architects of a new society.

Neruda uses powerful and vivid language to evoke the struggle and resilience of the Latin American people.

Images of nature (“meadows”, “sea”) contrast with those of violence and repression (“lumberjacks”, “carpenters”).

Rhythm and musicality: The poem has a dynamic, almost incantatory rhythm that invites participation and action.