↑

Ásma Asmáton text of Iákovos Kambanélli

Ómorfī pólī text of Yiannis Theodorakis

Dakrysmena matia text of Yiannis Theodoraki

Ena to helidoni text of Odyseas Elytis

Ásma Asmáton – Song of Songs

⇑

|

Τι ωραία που είν’ η αγάπη μου, |

How beautiful is the beloved of my soul, |

|

με το καθημερνό της φόρεμα |

with her simple everyday dress |

|

κι ένα χτενάκι στα μαλλιά. |

and a small comb in her hair. |

|

Κανείς δεν ήξερε πως είναι τόσο ωραία. … |

No one in the world has ever known such beauty. … |

|

Κοπέλες του Άουσβιτς, |

Pretty girls of Auschwitz, |

|

του Νταχάου κοπέλες, |

pretty girls of Dachau, |

|

μην είδατε την αγάπη μου ? … |

have you not seen my beloved? … |

|

Την είδαμε σε μακρινό ταξίδι, |

We saw her on a long journey, |

|

δεν είχε πια το φόρεμά της |

stripped of her modest dress |

|

ούτε χτενάκι στα μαλλιά. |

and her little hair comb. |

|

Τι ωραία που είν’ η αγάπη μου, |

How beautiful is the beloved of my soul, |

|

η χαϊδεμένη από τη μάνα της |

blessed by her mother’s caresses |

|

και τ’ αδελφού της τα φιλιά. |

and her brother’s kisses. |

|

Κανείς δεν ήξερε πως είναι τόσο ωραία. … |

No one in the world has ever known such beauty. … |

|

Κοπέλες του Μαουτχάουζεν, |

O beauties of Mauthausen |

|

κοπέλες του Μπέλσεν, |

and beauties of Belsen, |

|

μην είδατε την αγάπη μου ? … |

have you not seen my beloved? … |

|

Την είδαμε στην παγερή πλατεία, |

We saw her, on the frozen square, |

|

μ’ ένα αριθμό στο άσπρο της το χέρι, |

with a number on her white wrist, |

|

με κίτρινο άστρο στην καρδιά. |

and a yellow star on her heart. |

|

Τι ωραία που είν’ η αγάπη μου, |

How beautiful is the beloved of my soul, |

|

η χαϊδεμένη από τη μάνα της |

cherished by her mother’s caresses |

|

και τ’ αδελφού της τα φιλιά. |

and her brother’s kisses. |

|

Κανείς δεν ήξερε πως είναι τόσο ωραία. … |

No one in the world has ever known such beauty. … |

Asma asmaton (Song of Songs) is the first in a cycle of four songs which together form the Cantata (or Ballad) of Mauthausen.

This cycle was inspired by a book by Iakovos Kambanellis, recounting the story of life and death in the Nazi concentration camp at Mauthausen, Austria, where large numbers of Jews and other prisoners were held during World War II.

The four songs of Mauthausen have a common theme. They express in powerful music and lyrics the terror, agony, and torture of the concentration camps and their effects on the minds and bodies of the prisoners.

The best known of the four songs is Asma asmaton, which describes the love between two Jewish prisoners in the Mauthausen concentration camp and expresses the prisoner’s anguish upon learning that the woman he loves has just been taken to the gas chamber.

Maria Farantouri, the Greek singer, gives a poignant interpretation of this lamentable daily life, which has the refrain “How beautiful is my love” and was taken from the song of Solomon.

Equally emotional is the fourth song in the cycle, Otan Teliosi o Polimos (When the War Ends). Life in death for the interned Jews who dreamed of the end of the war or of life being nothing more than surreal images.

To the girl he saw only through the barbed wire that separated them and held them prisoner, “the girl with terrified eyes and frozen hands.” He calls out to her: “Don’t forget me, wait for me, and finally we can meet, kiss, and walk in the sunny streets” that seem normal with ordinary people… when the war is over… or when we meet in the gas chamber.

Exile is a situation fraught with emotions: separation, love, anticipation, hope, etc.

The lyrics and music can transport the listener to their own personal exile.

Since ancient times, immigration and exile have played a central role in Greek life.

In a continuous movement, the character of Ulysses remains the diachronic symbol of an entire people, through its traditions and music.

Since ancient times, Greeks have lived and died in exile in foreign lands or in their own country, because of an idea, a belief, or simply to seek a better life. From the creation of the colonies of Magna Graecia around the Mediterranean to the tragic events experienced by the Greeks in the 20th century, when the entire population was scattered across five continents, they lived like Ulysses, whether conscious of their fate or not.

However, for them, “strangers and the needy are the adopted children of Zeus, and we learn that they are also part of our family” and

“there is nothing sweeter for a man than his homeland and his family” (Odyssey, Book VIII).

This sacred character of the person of the Stranger is also highlighted by the hymnology of the Orthodox Church, which attributes the status of Stranger to Jesus Christ:

Give me this Stranger who, from childhood, was exiled as a stranger.

Give me this Stranger whom his own people condemned to death, hating him as a stranger.

Give me this Stranger who knows how to welcome the poor and strangers into himself.

The book “Mauthausen” recounts the author’s imprisonment in the Austrian concentration camp from 1943 until the camp’s liberation in May 1945. The author reflects on his survival and also on the months following the liberation by the Americans, asking the fundamental question, as other authors who survived (notably Primo Levi) have done, in the following way: how is it possible to save a part of humanity in the heart of hell?

In 1942, under German occupation, Iakovos Kambanellis sought to flee to the Middle East. Finally deciding to cross into Switzerland, he ended up being arrested in Innsbruck, Austria. He was then sent to the Austrian concentration camp at Mauthausen, where he was interned from 1943 until May 5, 1945, when the camp was liberated by American troops.

Here is how Iakovos Kambanellis recounted in 2005 how he ended up in Mauthausen:

“A friend, a little older than me, convinced me that we could escape from Greece to the Middle East. He was more determined than I was and set about finding a way: we would go to one of the coasts of Attica where caiques would take us across. This didn’t work out because he realized that each of us would need 60 pounds of gold. When he saw that this wasn’t going to work, he found another way: we would cross through Yugoslavia with papers and arrive in Vienna where, with the 200 marks we would have earned selling cigarettes, we would obtain fake Italian passports. That’s what we did. They arrested us in Innsbruck and took us to a prison in Vienna. The easiest thing to do was to send you to a concentration camp. And that’s what happened…”

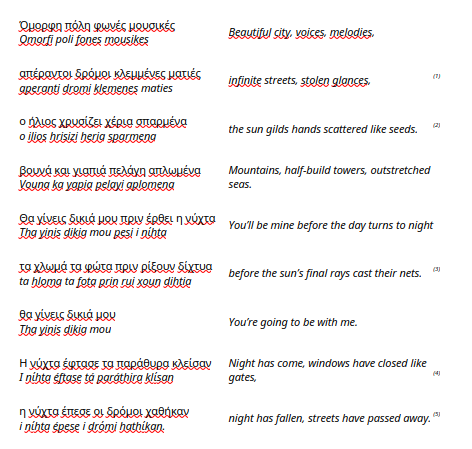

Ómorfī pólī: Beautiful city

(1) The Greek words in these lines offer flashes of visual and auditory imagery, a standard poetic strategy. They do not have the grammatical structure (ex. subject-verb-object) of a sentence.

(2) σπαρμένα [sparmena] literally translates as « sown » or “scattered”. Either of those words by itself seemed to us to invite possible misreading in English and also to be insufficiently imagistic, not to mention off-key musically.

(3) νύχτα [nihta] and δίχτυα [dihtia] is an almost-perfect rhyme in Greek. Here a literal English translation of those words (“night” and “nets”) works very well. But getting those words to occur as line-endings required some departure.

(4) κλείσαν = “they closed”. We included the simile “like gates” so that the verse ends with a rhyming couplet, as it does in the Greek original. The Greek verbs in this verse are in the simple past tense, creating a sense.

(5) χαθήκαν [hathίkan] = « they were lost » or « they got lost. » The word has the same variations in meaning as in English: to misplace, to feel disoriented\hopeless, and to die.

Composed in 1950 or 1952 based on a poem by his brother Yannis and entitled Όμορφη πόλη [Omorfī polī] (Beautiful City), this piece is the first of four songs in his cycle Λιποτάκτες [Lipotaktes] (Deserters).

Theodorakis discovered Greek folk music just as he was gaining entry into the circle of internationally recognised young composers.

With this work, he initiated the renaissance of Greek music and sparked a cultural revolution in his homeland, the consequences of which are still felt today.

It has been recorded in 1961 by Theodorakis himself.

And here is the version by Νένα Βενετσάνου [Nena Venetsanou], recorded in 1994.

From then on, the Greek right wing considered Theodorakis one of its greatest threats.

When Dr Grigoris Lambrakis was assassinated in May 1963, Theodorakis founded the Lambrakis Democratic Youth (Lambrakides) and became its leader.

Under his leadership, it became the strongest political organisation in Greece, with 50,000 members.

In 1964, Theodorakis was elected to parliament and, together with the Lambrakides, founded more than 200 cultural centres across the country.

He composed one work after another, using the most beautiful texts from 19th- and 20th-century Greek literature.

Edith Piaf also sang Theodorakis, in Raymond Rouleau’s film Les amants de Teruel (France, 1961, released in 1962).

It is an astonishing, dance-filled film, whose visual impression evokes certain surrealist paintings, notably those of Dali. It is in fact a film adaptation of the eponymous ‘ballet-drama’ conceived and directed by Raymond Rouleau himself, with music by Theodorakis. The ballet was created in 1959 in Paris by Ludmila Tcherina and her company, who are also the protagonists of the film. We do not know to what extent the dance sequences in the film reproduce the choreography of the original ballet, nor whether the ballet’s music is reproduced in its entirety in the film (for which connecting music, described in the credits as ‘metaphonic composition’, was commissioned from Henri Sauguet); in any case, the main musical theme of the film, which is heard in the credits and then returns as a leitmotif, was added.

It was on this theme that Edith Piaf recorded the song Les amants de Teruel in 1962, under the direction of Theodorakis himself, with lyrics by Jacques Plante. However, this theme was not an original composition by Theodorakis, who in fact simply recycled an earlier work for Les amants de Teruel.

⇑

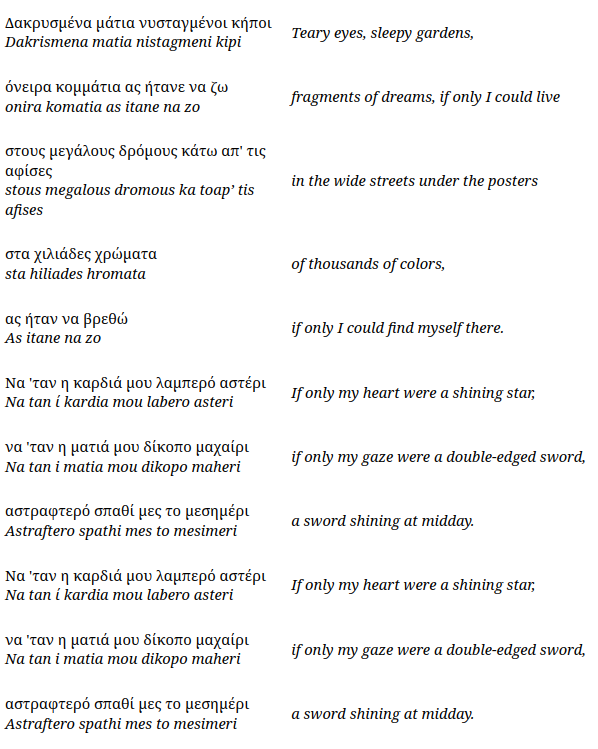

Dakrismena matia : Teary eyes

Composed to a poem by his brother Yannis and entitled Δακρυσμένα μάτια [Dakrysmena matia] (Teary Eyes), this piece is the second of four songs in his cycle Λιποτάκτες [Lipotaktes] (Deserters).

⇑

Ena to helidoni – The Swallow

| Ενα το χελιδόνι κι η άνοιξη ακριβή Ena to chelidoni ki i anaixi akrivi |

Just one swallow and spring is punctual, |

| Για να γυρίσει ο ήλιος θέλει δουλειά πολλή. Yia na yirisi o ilios theli doulia polli. |

For the sun to turn, much work is required. |

| Θέλει νεκροί χιλιάδες να ‘ναι στους τροχούς Theli nekri chiliades na ‘ne stous trohous |

Thousands must die to turn the wheel, |

| Θέλει κι οι ζωντανοί να δίνουν το αίμα τους. Theli ki i zontani na dinoun to aima tous. |

And the living must give their blood. |

| Θεέ μου πρωτομάστορα μ’ έχτισες μέσα στα βουνά Thee mou protomastora m’ ehtises mesa sta vouna |

My God, Master Builder, you have walled me in the mountains, |

| Θεέ μου πρωτομάστορα μ’ έκλεισες μες στη θάλασσα. Thee mou protomastora, m’ eklises mes sti thalassa. |

My God, Master Builder, you have locked me at the bottom of the sea. |

| Πάρθηκεν από μάγους το σώμα του Μαγιού, Parthiken apo magous to soma tou mayiou, |

He was taken by magicians, the body of May. |

| Το ‘ χουνε θάψει σ’ ένα μνήμα του πέλαγου. To ‘ houne thapsi s’ ena mnima tou pelagou. |

They buried it in a tomb in the sea. |

| Σ’ ένα βαθύ πηγάδι το ‘ χουνε κλειστό S’ ena vathy pigadi to ‘ houne klisto |

In a very deep well they kept him prisoner. |

| Μύρισε το σκοτάδι κι όλη η άβυσσος. Myrise to skotadi ki oli i avissos. |

He perfumed the darkness and the entire abyss. |

| Θεέ μου πρωτομάστορα μέσα στις πασχαλιές και εσύ Thee mou protomastora mesa stis pashalies ke esy |

My God, Master Builder, in the lilacs of Easter, you too, |

| Θεέ μου πρωτομάστορα μύρισες την ανάσταση. Thee mou protomastora myrises tin anastasi. |

My God, Master Builder, perfumed the Resurrection. |

The song “Ena to helidoni” is taken from the oratorio that Mikis Theodorakis composed in 1964 based on the epic poem Axion esti by the poet Odysseas Elytis, published in 1960. In this ambitious musical work, the composer blended all kinds of music, including folk, choral, and orchestral.

The song of the swallow metaphorically evokes the Greek people’s struggle to regain their freedom and the promise of resurrection.

It became an anthem of resistance during the military dictatorship from 1967 to 1974.

Two video documents are among the most moving testimonies of the period of liberation that followed:

-

The first was recorded at the Karaiskaki Stadium in Falliro on October 9 and 10, 1974, shortly after Theodorakis’ triumphant return to Greece on July 24.

It is notable both for Antonis Kaloyannis’ performance and for the extraordinary fervor of the audience, who literally communed with Theodorakis’ music. -

The second, equally famous, was recorded in 1977 ay the Lycabettus Theater in Athens, with an Olympian Grigoris Bithikotsis.